“Afrofuturist Rashid Johnson’s Message To Our Folks” is the first post in the new column “Postcolonial Thoughts” written by artist Christopher Hutchinson, Assistant Professor of Art at Atlanta Metropolitan College and Archetype Art Gallery Owner in Atlanta, Ga. In the column Christopher will offer fresh and trenchant analyses of art and theory through the lens of multiple traditions, especially those neglected or not included in the Western canon.

by Christopher Hutchinson

Rashid Johnson earned his B.F.A. from Columbia College Chicago in 2000 and enrolled in the Master of Fine Arts program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2003. The program’s heavy emphasis on concept and theory posed a challenge to Johnson who wanted to make things. Yet it stoked his interest in the formal elements of artworks and in finding meaningful materials outside those typically associated with traditional art. Johnson left for New York in 2005, and currently lives and works in Brooklyn. Johnson was the recipient of the 2012 David C. Driskell Prize.

Rashid Johnson’s Message to our Folks exhibition at the High Museum was on display June 08 – September 08, 2012 and has recently moved to September 20, 2013 – January 6, 2014 at the Kemper Art Museum to great reviews. Viewers were asked to accept Johnson’s venture from photography to a hodgepodge of other mediums. Johnson’s venture includes carefully contrived compositions. These compositions are not as offensive in the medium of photography, where the medium itself is understood to be a simulation. Once Johnson includes sculpture, painting, installation, grafitti and video these compositions are painfully insulting. Johnson’s attempts at expression do not meet the requirements included in the freedom provided by abstract expressionism. Johnson’s marks are unresponsive, static moves. The expression here is purely decorative design. Johnson’s decisions aren’t concerned with the exploration of the praxis of art making.

UNDERGRADUATE

Johnson’s methodology is clearly an undergraduate approach. When a concept is weak, throw as many icons as possible. Undergraduates plow through ideas without taking into account the limitations of the medium. The medium dictates whether that idea will succeed, and when it doesn’t, undergrads depend on imagery to cover this oversight. Every medium requires a different process from concept to execution and often the concept conflicts with the material. Will this material allow this concept to work? Johnson presents forced concepts onto materials inorganically.

“Napalm” (2011) by U.S. artist Rashid Johnson. It will be shown by the London and Zurich dealers Hauser & Wirth at the 38th edition of the FIAC fair in Paris, previewing Oct. 19.

Johnson’s Napalm is a good example of this oversight. Napalm is just one example of the blatant disrespect Johnson displays in his praxis. Marks and mediums are made as an afterthought, not as an intuitive response. Every drip, every punch, every brand, every image is staged as an illustration of narrative. Johnson often employs an additive process. Adding more stuff does not make that idea any clearer. Johnson’s marks are timidly placed to make the photographer (which he is) comfortable. Broken glass is regularly spaced and spray paint drips are consistently spread out. It is problematic when an individual is having a discussion of materials, mark-making, sculpture, abstraction, and graffiti.

NOSTALGIA

Johnson explores the work of black intellectual and cultural figures as a way to understand his role as an artist as well as the shifting nature of identity and the individual’s role in that shift. By bringing attention to difference and individuality, he attempts to deconstruct false notions of a singular black American identity. (http://www.high.org/Art/Exhibitions/Rashid-Johnson-Message-To-Our-Folks.aspx)

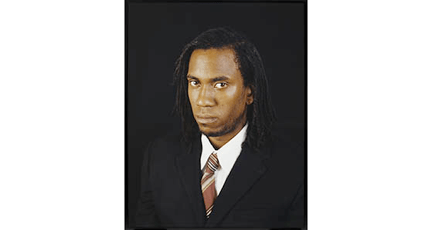

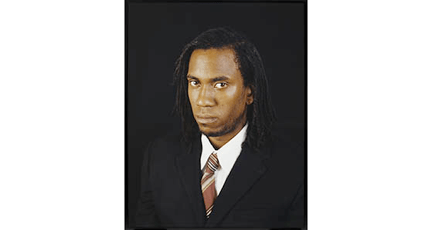

Self Portrait with My Hair Parted Like Frederick Douglass, 2003.Lambda print. Collection of Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of the Susan and Lewis Manilow Collection of Chicago Artists, 2006.26

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

Message to our Folks is laced with nostalgia. Don’t you remember Frederick Douglass, Al Green, Sweetback, Huey Newton’s wicker chair, Jazz, and Public Enemy? Johnson’s Self Portrait with My Hair Parted Like Frederick Douglass accurately sums up this exhibition. This seems like Black intelligence, this appears like authentic Blackness. It is a simile and if Johnson’s discussion included simulacra, he would have succeeded. This exhibition provides the foundation to include Blackness as a trend. It adopts osmosis of style, where all an individual has to do is “act Black” to be an authority on Blackness.

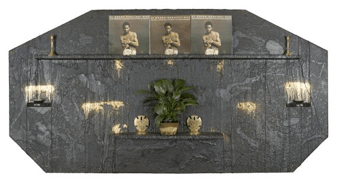

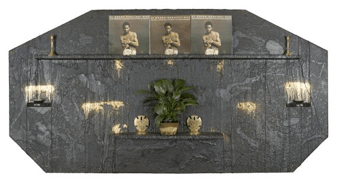

Triple Consciousness, 2009.

Black soap, wax, vinyl in album cover, shea butter, plant, and brass

48 x 96 in. (121.9 x 243.8 cm)

Collection of Dr. Daniel S. Berger, Chicago

Courtesy of the artist and moniquemeloche, Chicago

Nostalgia is a protective warm blanket that prevents this work from critique. How can you criticize the monolithic Black community and not be a deserter? The fact is, Johnson’s Triple Consciousness is just corny. Three Al Green albums does not address the Dubois’s Double Consciousness; it belittles it. The moment critical questioning is applied Johnson’s exhibition falls apart. Johnson’s work is the very definition of Black exploitation by Black Artists under the pretense of uplifting the community.

AFROFUTURISM

Here again we have a contemporary artist living in the past. The irony is Johnson and others are considered to be Afrofuturists. Doctoral candidate Nettrice Gaskins does her best to define and identify the Afrofuturist agenda.

What is afrofuturism?

• It’s not the black version of Futurism. It is an aesthetic and the term can be used to describe a type of artistic and cultural community of practice. Afrofuturism navigates past, present and future simultaneously. The keyword here is: navigation or ascertaining one’s position and planning and following a specific route.

• It is counter-hegemonic. Hegemony refers to the dominant, ruling class or system. Afrofuturism is not concerned with the mainstream or the canon of (Western) art history. In the image above jazz musician and cosmic philosopher Sun Ra (Ra being the Egyptian God of the Sun) placed himself at the center of other known cosmic philosophers and scientists.

• It is revisionist, meaning that afrofuturism advocates for the revision of accepted, long-standing views, theories, historical events and movements

While Gaskins provides the best analysis of Afrofuturism’s intent, unfortunately most of the visual artists included in the Afrofuturist dialogue succeed at accomplishing the exact opposite of its intent. Afrofuturism currently actually provides a collective generic consciousness, which Johnson has condoned. The canon of Afrofuturism imagery is there due to the lack of originality and the regurgitation of something that is assumed to be authentic “Blackness“. Afrofuturism, at best, is a style not an aesthetic. It is not a set of principles underlying and guiding the work of a particular artist or artistic movement. Afrofuturism is stuck navigating the past. Using the spectacle of black bodies dressed up in futuristic garb does not change the context that already exists. The spectacle nourishes it.

ECTO-KITSCH

Black artists manage their representations (images, sounds, systems) in mainstream society and the global world through creativity and innovation, and by using improvisation and re-appropriation to move beyond the limits of nationality or identity. We see these representations manifested again and again in black culture. The lack of African knowledge has not prevented African diasporic people from tapping into the ancestral memory of traditional (African) systems. In other words, we replaced images/artifacts like the cosmogram (map of the universe) with the Unisphere. (http://netarthud.wordpress.com/2013/09/16/what-is-afrofuturism/)

Ecto-Kitsch, a term coined by Professor Jason Sweet that addresses the globalization push that was initially a response to Postcolonialism, is a farce. Ecto-Kitsch recognizes the pretense that a globalization is a non-Western interpretation of art produced by minorities. It recognizes that Globalism has created a universal rubric used to qualify art from non-Western people through the lens of the West. The most Western-like minorities are pushed to the forefront as an example of the West’s new inclusive attitude. The Unisphere expressed in Afrofuturism equals hegemony and hegemony equals kitsch. The very images/artifacts posed as re-appropriations in Afrofuturism, are used for commodification of living people. Johnson proves this commodification with his New Black Yoga. A Black man is performing yoga poses on a T.V placed on a persian rug with the words black yoga spray painted in gold on the rug. This is by far the worst piece in the exhibition. Now Johnson ventures into commodifiying other non-Western cultures as well as his own. This is Johnson’s Message to our Folks.

Christopher Hutchinson is an Assistant Professor of Art at Atlanta Metropolitan State College and Archetype Art Gallery Owner in Atlanta, Ga. He received his Master of Fine Arts Degree in Painting from Savannah College of art & Design, Atlanta and his Bachelor of Arts Degree from the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Alabama. He lived in Alabama for 10 years before moving to Atlanta in 2008. His installations mostly consist of black folded paper airplanes.

Christopher Hutchinson is an Assistant Professor of Art at Atlanta Metropolitan State College and Archetype Art Gallery Owner in Atlanta, Ga. He received his Master of Fine Arts Degree in Painting from Savannah College of art & Design, Atlanta and his Bachelor of Arts Degree from the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Alabama. He lived in Alabama for 10 years before moving to Atlanta in 2008. His installations mostly consist of black folded paper airplanes.

Learn more about Christopher and his work at Black Flight 144.

“A sound theater of Negro prison work songs will be played to wake up the souls of Negro men that were forced to lay the tracks in and around Atlanta as the re-enslavement of Black Americans increased during the Civil War up to World War II. Most of these free men were imprisoned on bogus charges enforced by Penal Labor/Servitude laws allowing the cycle of supremacy to continue. The inspiration for this sound work came from the pages of Slavery by Another Name written by Atlanta author and Pulitzer Prize-winner Douglas A. Blackmon.”

“A sound theater of Negro prison work songs will be played to wake up the souls of Negro men that were forced to lay the tracks in and around Atlanta as the re-enslavement of Black Americans increased during the Civil War up to World War II. Most of these free men were imprisoned on bogus charges enforced by Penal Labor/Servitude laws allowing the cycle of supremacy to continue. The inspiration for this sound work came from the pages of Slavery by Another Name written by Atlanta author and Pulitzer Prize-winner Douglas A. Blackmon.” Meko’s wailing sounds envisage a time that is past and present as a continuum. It was a confrontation with the dead, not just the physicality of death, but also the innate that died to become more academic. What awakened was the “Id.”

Meko’s wailing sounds envisage a time that is past and present as a continuum. It was a confrontation with the dead, not just the physicality of death, but also the innate that died to become more academic. What awakened was the “Id.” Christopher Hutchinson is an Assistant Professor of Art at Atlanta Metropolitan State College and Archetype Art Gallery Owner in Atlanta, Ga. He received his Master of Fine Arts Degree in Painting from Savannah College of art & Design, Atlanta and his Bachelor of Arts Degree from the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Alabama. He lived in Alabama for 10 years before moving to Atlanta in 2008. His installations mostly consist of black folded paper airplanes.

Christopher Hutchinson is an Assistant Professor of Art at Atlanta Metropolitan State College and Archetype Art Gallery Owner in Atlanta, Ga. He received his Master of Fine Arts Degree in Painting from Savannah College of art & Design, Atlanta and his Bachelor of Arts Degree from the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Alabama. He lived in Alabama for 10 years before moving to Atlanta in 2008. His installations mostly consist of black folded paper airplanes.