Spotlight: Interview with the Atlanta TAR (Therapeutic Artist Residency) participants

by Melissa D. Johnston

A few months ago, Atlanta artist and former Creative Thresholds contributor Julie L. Sims contacted me about an exhibition associated with a residency she’d done the year before in Atlanta called TAR (Therapeutic Artist Residency). The TAR project is new to Atlanta and Julie is one of its inaugural artists. The vision of artist and licensed therapist Orion Crook, TAR aims to create a deeper level of support for its artists by exploring the intersection between art and therapy. Each artist in the program receives monthly 2-hour group and individual therapy sessions. The main focus of the residency is to analyze the artist’s process and how that process parallels other life processes and vice versa.

A few months ago, Atlanta artist and former Creative Thresholds contributor Julie L. Sims contacted me about an exhibition associated with a residency she’d done the year before in Atlanta called TAR (Therapeutic Artist Residency). The TAR project is new to Atlanta and Julie is one of its inaugural artists. The vision of artist and licensed therapist Orion Crook, TAR aims to create a deeper level of support for its artists by exploring the intersection between art and therapy. Each artist in the program receives monthly 2-hour group and individual therapy sessions. The main focus of the residency is to analyze the artist’s process and how that process parallels other life processes and vice versa.

The residency ends with an artist showcase in two parts. The first exhibition, Parallels: Holding Space, held in May 2017, highlighted the work of the artists of TAR as individuals after their year of intense personal and collective art making and reflection. The second exhibition, Parallels: Unfolding Space, takes place in three parts and begins tonight, July 27, 2017. This second exhibition branches out to bring the audience into an experience of TAR for themselves.

The TAR project is a wonderful experimentation with finding the deep support needed to do art as/in dialogue with ourselves, our fellow artists, and the culture at large. In the interview below, Orion and the artists share some of their experiences in the program. If you happen to be in the Atlanta area, check out one of the Parallels: Unfolding events. All are held at Day & Night Projects, 585 Wells St. SW, Atlanta, GA 30312. “Connect” is today, July 27, 7-10 pm. “Unfold” is August 3, 7-10 pm. “Release” is August 10, 7-10. The exhibition is on view from July 27-August 19, 2017. For more information, go to OrionPsychotherapy.org or contact OrionPsychotherapy@gmail.com.

1. As part of TAR, each of you participated in monthly individual and group therapy sessions, designed at least in part to explore the relationship between life, art, and therapy. Did anything surprise you in the exploration of that relationship?

ORION: Just tonight I was saying that I am still kind of in awe that this residency actually exists. I had an idea nearly three years ago, and now as we begin to close out the first year I can’t help but think, “This may have changed these people’s lives.”

XENIA: While an obvious concept to me now, it was surprising when I first started realizing that the way I dealt with my art mirrored the way I dealt with life and myself in general. Parallel structures started showing up, which brought forth a more integrative experience of life and art. It became clear that my art was accessing that relationship, using art processing to digest life’s processing.

JULIE: I wouldn’t say this was surprising to me, exactly, but I did realize how alike the mental tools of therapy and the mental tools of being an artist are. I guess there are some artists out there who are completely confident and never doubt their work or have to turn off that nagging critical voice, but most of the ones I know and even the famous ones I’ve heard speak describe their own struggles with doubt over whether their work is any good or not, even if they aren’t people who otherwise have problems with self-doubt in the rest of their lives.

You figure out how to work around that if you want to keep making art, and the most successful ways of doing so have a lot in common with therapeutic techniques designed to defeat negative self-talk and break destructive thought patterns. Therapy teaches you to be kinder to yourself, and you will need to be in order to have the resilience for rejection that is just part of being an artist.

2. Do you believe that empathy is part of the artistic process in general? In your own art? Has your understanding of empathy and its relationship to art changed after your experience with TAR?

ORION: Empathy is part of the human experience. I imagine that it comes across in multiple ways for the artist, but in particular when the artist imagines themselves as the viewer they are digging into how (they perceive) the other feels. This is influenced by what they bring focus to, and highlights their own cognitive structures. Does the artist believe the viewer or peer to be critical, supportive, emotional, aesthetic, and so on? How does this influence their art making process? My hope is that the residents were able to become more aware of their cognitive structures and how they influence their own empathetic viewing. Empathy is a skill that can be honed in on and developed as much as it can be skewed by the mind’s telling of a story. What I find important is that, as the artist becomes aware of their cognitive distortions, they are granted access to more authentic empathy underneath which enhances their relational experience.

XENIA: I think for the longest time I fought empathy in myself, and art process is in a way being in dialogue with yourself. I can’t speak to empathy being present in every artist’s process, but for me it became an element I’ve had to embrace in order to progress in my art. Coming into the residency, my expectations of my work and myself were so rigid, I was being hindered and limited in so many realms. Through the group process of TAR, empathy made its way into my personal work and approach to art, which eventually started opening more creative possibilities.

JULIE: I do believe that empathy is part of creating and understanding art. In general, I think art is a way to give expression to something an artist feels inside themselves, so when a viewer connects with a work of art they are experiencing a kind of empathy to the artist’s intent. Sometimes art takes that even further and is made with a voice expressly meant to foster empathy for specific causes, conditions, or groups of people. In my own series, Uncharted Territory: Anatomy of a Natural Disaster, I reference how we respond to people who have experienced a natural disaster as a parallel for how we should respond to people with mental health issues, and that work is in part intended as a pathway toward empathy for conditions that are often misunderstood or mischaracterized.

STEVE: If empathy is a kind of communication or understanding that is felt, rather than thought, then artists excel at empathy. Artworks can operate both in a realm of language and in the ineffable—and this precognitive space is also where empathy occurs.

Empathy’s flip side is judgement. In a group therapy situation, you learn to stop judging your neighbor, and to listen and allow yourself to experience what that person is saying.

3. The first TAR exhibition, Parallels: Holding Space, showcased your work as individuals after a year of personal and collaborative art-making and reflection. The second exhibition, Parallels: Unfolding Space, is a collaboration not just with each other, but also with the people attending the show. Your experience with TAR seems to be an ever-expanding circle touching people well beyond the work of an individual artist. What do you hope to accomplish in that connection?

ORION: We are letting people inside TAR, and I hope to establish a lighthouse for the art culture in Atlanta that stands for supporting our artists on a deeper level. The whole year is an extremely intimate experience; therapy comes with a lot of confidentiality. This second show is an expression of what it was like inside TAR. I mean that for better and worse, with expansion and vulnerability. We worked to unfold an experience of art that exists inside a particular container. This residency was contained with therapeutic intent, and this is being brought to the three nights, Connect-Unfold-Release. In the first night, the viewer gets to experience layers of the residency that help them connect with themselves.

XENIA: I think part of the intention of TAR was to build a creative community that saw value in and benefited from the interdisciplinary exploration of art and therapy. Going through the residency magnified the communal aspect, and made clearer that TAR sought to establish a new art culture. Connecting with other artists, viewers and anyone in the community that has an interest, is the residency’s way of doing just that.

JULIE: I am always wanting to normalize conversation about mental health. Between uneven insurance coverage for treatment and societal stigma, many people can’t afford or will never seek out a therapeutic relationship, which is a shame, because it’s something I think nearly everyone could benefit from. This exhibition is an opportunity to share some of that experience, to show how it intersects with other aspects of life, and perhaps overturn assumptions about what therapy can be.

4. “Space”—understood both metaphorically and literally—plays a large role in the description of the TAR program and even appears in the title of both exhibitions. After your year together, how do you understand “space” in relation to the artistic and therapeutic process? Does it play a role in your own individual art?

ORION: Therapy is an art form in the practice and performance of the science of psychology. I see myself as a space holder when I step into the therapeutic relationship. It it my job to curate a space that allows for unconditional positive regard, vulnerability, safety, risk taking, confrontation, and in the end a therapeutic intent. Therapeutic intent is a large concept, but it means in this moment for me that after we process and go deep we gather awareness of what is in front of us and make a choice to move forward, towards the growth work, towards connecting, and often doing what is hard but supports us to be the self we want to be in the future.

XENIA: Space is my medium; and everything I do revolves around the visceral experience of it. Expressing mental spaces into physical ones through metaphor is what I was developing before TAR, even if it was not as clear to me then. After a year in the residency my relationship with space has only deepened more. I now understand it as something necessary to any process. Whether it is artistic or therapeutic in nature, space is what gives room for that process to unfold. It is something fluid that shifts to the process’s needs, and experienced on multiple levels. Throughout this year, I have learned to expand and retract myself accordingly, adjusting to my life and my creative process.

JULIE: When you “hold space” for someone you are allowing them to be just as they are without judgment or trying to change their feelings. You’re giving them room to express their truth. Artists have to remember to hold space for themselves. If you judge every thought and impulse as they arrive, if you try and change what you’re doing to something you think you should do instead of what is true to yourself, you’re not holding space for your work to develop.

Our first exhibition, Holding Space, let each of us be as we are and express our own truths. In Unfolding Space we are opening up a new dimension and creating a wholly new space collaboratively, and we’re inviting other people to let us hold that space for them to step into.

STEVE: When Sun Ra sings “space is the place,” he’s equating Outer Space with the freedom to become what you will be, where imagination is the force that creates the world.

One of Google’s definitions of space is “a continuous area or expanse that is free, available, or unoccupied.” This can mean allowing physical and mental space for your collaborator to do their thing—to trust that your colleague is going to make a contribution that is amazing and unexpected.

Another definition is “the dimensions of height, depth, and width within which all things exist and move.” In this sense, I see the art gallery as that container, and I am covering the gallery walls with burlap as a way to contain, focus, and amplify the energy of what we do in there.

5. The sacred or language associated with the sacred plays a role in the discourse about TAR’s projects. The visitors to the second series of exhibitions (Parallels: Unfolding Space) will participate in shared rituals designed by the artists, ultimately aimed toward the process of healing. The last show ends with the artist as “sacred practitioner” inviting people to join her in washing away their troubles in a tank of salt water with the intention to begin anew. Do the processes of art-making and/or therapy contain aspects of the divine (however understood) for you? If so, what do you see as the connection?

ORION: This is a great question and one that brings a beautiful tension between the anchor of this series and our perspectives. I come from a poly truth perspective that finds comfort in having a practice that does have a relationship with the creation force. Due to a frontal cortex, I as a human have the ability to believe that the divine doesn’t exist, that it doesn’t matter whether I believe it or not because I can never “truly know,” that it does exist, and that believing has its own affect whether it exists or not. I can hold all of these as truths and still exist, I actually believe it’s how the brain works on its own. We often find ourselves going between things, back and forth questioning our assumptions. The brain struggles to hold onto one side of such a large topic and just stay settled there. When I come from a perspective that makes space for all of the viewpoints around the divine, I get a sense of freedom that deals less with having to choose, and allows me to focus more on how I want to live and act. For me, whether the divine as you name it exists or not, I enjoy practicing from a perspective that is in relationship to a possibility that I can influence change, that my will is worth casting in intentional directions, and that art is a medium for materializing this process.

JULIE: For me art is sacred in the sense that it is the soul of who I am. I experience art-making as a force of creation, which some people associate with divinity, although I do not. I see it as tapping into the systems that drive the universe… creation, evolution, destruction. Performance art has a very blurry line with ritual, so conflating the two feels very natural. I think rituals have value separate from religious intent—the daily routine performed exactly the same every day is a type of ritual that offers control and continuity in a world that often lacks either. So, I would not say that either sacredness or ritual are divine.

This specific performance will mark a year since my breast cancer diagnosis, and is a performance-art-ritual with the ultimate intent of “letting go.” As such, it sits directly at the intersection of art and therapy, because it is using art as a vehicle to process and release a life experience.

STEVE: More than the words sacred and divine, I’m interested in the concepts like spirit and energy. We encounter these when out in the forest, in the desert, or in the ocean; or when we meditate, or make art, or do drugs. Any situation where we experience flow is when we’re connecting to the energies that are all around us and within us.

The processes that we’re exploring and introducing to our audiences—connecting, unfolding, releasing—are ways of breaking through barriers in our selves. When we can bring down these walls, we find ourselves closer to that spirit that we so rarely glimpse.

XENIA: I do not feel connection with the language of sacred or divinity as much as I do with the concept of being in touch with oneself. I experience this while making art. I believe at times, through our process we can experience moments of calm, and a sense of faith in ourselves and in the work. Those moments could be described as divine; but in no way do I see the artist as sacred or divine. I am simply tapping into something that already exists. As far as ritual, while it often is associated with religion, our intention came from a more meditative approach. The repetition of a task while holding a certain idea in place, the overlay of a movement solidifying it; over and over and over. This is seen in performance often and I think ritual can exist within that realm.

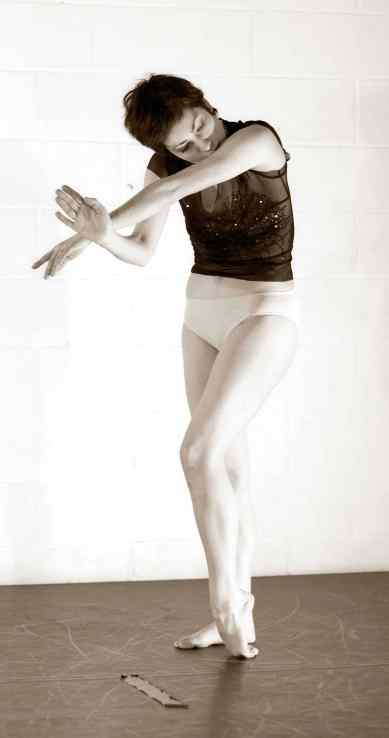

The TAR group, working hard on their new performance and installation-based show Parallels: Unfolding-“Connect.” From left: Xenia Simos, Steven L. Anderson, Julie L. Sims, Orion Crook

Julie L. Sims lives in the Atlanta area and graduated summa cum laude from Georgia State University. Her work has been exhibited nationally and locally, and has been written about in Creative Loafing, ArtsATL.com, and in publications including Possible Futures’ Noplaceness: Art in a Post-Urban Landscape. She is a 2016–15 TAR Project resident, and was a 2014 WonderRoot CSA artist, a 2013–14 Walthall Fellow, was selected by the New York Times to attend the New York Portfolio Review (2013), and was nominated for the Forward Arts Foundation Emerging Artist Award (2012). See more at lensideout.com.

Steven L. Anderson is a founding member of Day & Night Projects, an artist-run gallery in Atlanta. Anderson has been a Studio Artist at Atlanta Contemporary (2013–16), a 2015 Hambidge Center Distinguished Fellow, and a 2014–15 Walthall Artist Fellow. Anderson’s notebooks are in the permanent collection of the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University. He has exhibited in Atlanta, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, Miami, and Chicago. More information at www.StevenLAnderson.com.

Xenia Simos is an installation artist with a background in sculpture and design. A graduate of the University of Georgia with a bachelor of fine arts in interior design, her work explores space and our relationship to it. Through a conceptual and process-based approach, Simos translates the human experience into a spatial composition, manifesting mental structures into physical ones. Her works are often site-specific, and interdisciplinary in medium.